Among all reptile families on Earth, few inspire as much curiosity and wonder as the Chameleónovité — the scientific family Chamaeleonidae, known in English as chameleons. These extraordinary creatures have captivated scientists, nature enthusiasts, and pet owners alike with their distinctive eyes, remarkable camouflage abilities, and elegant slow movements that embody both mystery and grace.

The term Chameleónovité refers to the entire family of chameleons, comprising over 150 species distributed primarily across Africa, Madagascar, southern Europe, and parts of Asia. Famous for their color-changing skin, independently moving eyes, and sticky projectile tongues, chameleons represent one of the most specialized evolutionary branches of the reptile world.

In this in-depth article, we’ll explore everything about Chameleónovité: their taxonomy, anatomy, behavior, ecology, threats, and even their suitability as exotic pets. By the end, you’ll understand why these creatures are not just nature’s curiosities but essential components of the ecosystems they inhabit.

The Origins and Classification of Chameleónovité

The word “Chameleónovité” comes from the Slovak (and other Slavic) term for the family Chamaeleonidae. In biological taxonomy, this family falls under the order Squamata, which also includes lizards and snakes.

Chameleónovité are unique within their order because of their specialized arboreal lifestyle. Most species are tree-dwellers, equipped with strong grasping limbs and prehensile tails designed to navigate branches with precision and balance.

These reptiles are most diverse in Madagascar, home to about half of all known species. Africa hosts a large portion of the remaining species. At the same time, smaller populations exist in southern Europe (such as the common chameleon, Chamaeleo chamaeleon), the Middle East, and South Asia (including India and Sri Lanka).

Their diversity reflects millions of years of adaptation to various habitats from dense rainforests to dry savannas making the Chameleónovité a powerful example of evolutionary specialization.

Anatomy and Unique Physical Adaptations

The members of the Chameleónovité family possess some of the most extraordinary anatomical features in the animal kingdom. Their adaptations have made them efficient predators and skilled survivors in complex environments.

Independent Eyes and Panoramic Vision

One of the most recognizable traits of chameleons is their eyes. Each eye can rotate independently, allowing a single chameleon to look in two different directions simultaneously. When prey is spotted, both eyes focus together, creating precise depth perception. This combination gives them nearly 360-degree vision and an incredible hunting advantage.

Projectile Tongue

A chameleon’s tongue is a marvel of biological engineering. It can extend to nearly twice the animal’s body length in less than a second. The sticky tip of the tongue captures unsuspecting insects with astonishing speed and accuracy, a mechanism that makes them among the fastest hunters in the reptile world relative to size.

Zygodactylous Feet and Prehensile Tail

The feet of Chameleónovité are perfectly adapted for grasping branches. Each foot has two groups of fused toes two on one side and three on the other — forming a strong “clamp.” Along with their muscular, prehensile tails that act like a fifth limb, these features enable them to climb trees and maintain stability even while hunting or sleeping.

Color Change and Communication

Perhaps the most famous ability of chameleons is their capacity to change color. Contrary to popular belief, this isn’t solely for camouflage. Color changes also express mood, temperature, light exposure, and social signals during courtship or territorial displays.

This phenomenon is made possible by specialized skin cells called chromatophores and iridophores, which contain pigments and reflect light differently. A calm chameleon may display shades of green or brown, while an agitated male may flash vivid yellows, reds, or blues.

Size and Variation

Chameleónovité species vary dramatically in size — from the tiny Brookesia micra, which can sit comfortably on a match head, to the large Furcifer oustaleti, reaching lengths over 60 cm. Despite their differences, they all share a similar body plan: laterally compressed bodies, rotating eyes, and that unmistakable, slow, rocking movement.

Behavior and Lifestyle

Chameleons are mostly solitary creatures. They spend their lives climbing trees or shrubs, moving cautiously to avoid predators. Their motion, often swaying gently like leaves in the wind, serves as camouflage and makes them nearly invisible in their surroundings.

Diet and Hunting

The Chameleónovité family is primarily insectivorous. They hunt flies, crickets, grasshoppers, and other small arthropods. Larger species may occasionally consume small birds, lizards, or even rodents. Their hunting method spotting prey with laser-sharp precision and then launching their elastic tongue — is one of the fastest and most efficient predatory techniques among reptiles.

Reproduction and Lifecycle

Chameleons reproduce sexually, and depending on the species, they may be oviparous (egg-laying) or ovoviviparous (giving birth to live young). Females often lay eggs in moist soil or leaf litter, and incubation periods can range from several weeks to many months.

The lifespan of a chameleon depends on its species and environment. Smaller chameleons may live only 2–3 years, while larger ones, such as the veiled or panther chameleons, can live 5–10 years in captivity with proper care.

Communication

Although silent, chameleons are expressive through color and posture. A bright male showing intense coloration may be asserting dominance or attracting a female, while dull colors can signal submission or stress. In some cases, color change helps regulate body temperature darker tones absorb heat, while lighter ones reflect it.

Ecological Importance of Chameleónovité

In their ecosystems, chameleons play a vital ecological role. They control insect populations, maintaining balance within their food webs. In turn, they serve as prey for birds, snakes, and mammals. Their presence often indicates a healthy, biodiverse habitat.

In Madagascar, especially, chameleons have become symbols of environmental conservation. Because many species are endemic found nowhere else on Earth — their well-being directly reflects the condition of the island’s fragile ecosystems.

Threats and Conservation

Despite their adaptability, chameleons face numerous threats in the wild. Habitat destruction from logging, agriculture, and urban expansion continues to shrink their natural territories. Many species are also victims of the illegal pet trade, where wild-caught individuals are sold globally.

Climate change poses another danger, altering temperature and humidity patterns critical to their survival. Some populations have already begun declining due to these combined pressures.

To combat these issues, chameleons are protected under CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species). Conservation programs in Madagascar, Africa, and Asia aim to preserve habitats and promote sustainable captive breeding rather than wild collection.

Chameleónovité as Exotic Pets

Keeping a chameleon can be rewarding, but it also demands responsibility. These reptiles are sensitive to environmental changes and stress easily. Unlike dogs or cats, they are not animals that enjoy handling or social interaction.

Habitat and Environment

A chameleon’s enclosure should resemble its natural habitat: tall, well-ventilated, and filled with climbing structures and live plants. Temperature gradients are crucial — warm basking areas (around 30 °C) and cooler zones allow them to regulate body heat. Proper humidity (50–80%) and UVB lighting are also essential for health and calcium absorption.

Diet and Nutrition

Captive chameleons thrive on a diet of live insects such as crickets, roaches, and grasshoppers, dusted with calcium and vitamin supplements. Fresh, clean water is necessary, usually provided through misting systems or drippers, since chameleons prefer to drink droplets rather than still water.

Behavior and Stress

Stress is one of the biggest challenges in keeping chameleons. Frequent handling, poor enclosure design, or incorrect humidity can quickly lead to illness. Because each species has unique care requirements, prospective owners must research thoroughly before adopting one.

Common Species within the Chameleónovité Family

Some of the most popular and scientifically significant species include:

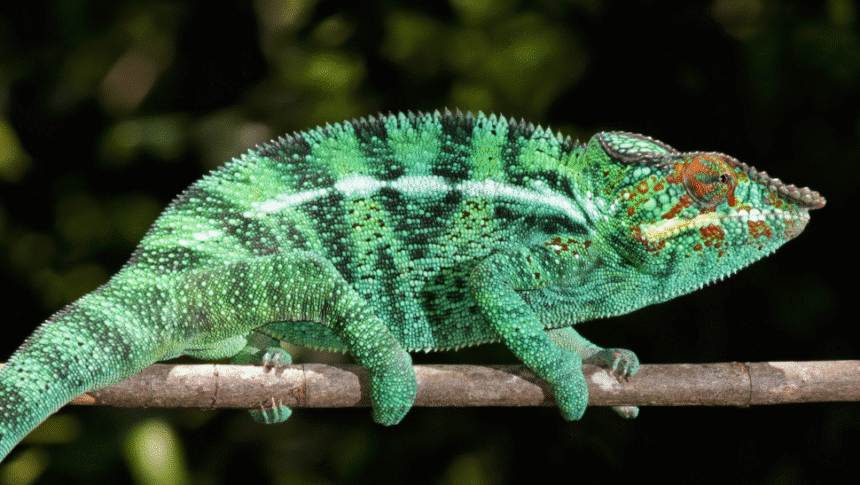

- Furcifer pardalis (Panther Chameleon) — native to Madagascar, renowned for its vibrant colors and popularity among breeders.

- Chamaeleo calyptratus (Veiled or Yemen Chameleon) — known for its striking casque on the head and relative hardiness in captivity.

- Trioceros jacksonii (Jackson’s Chameleon) — easily recognized by the three horns on males, reminiscent of miniature triceratops.

Each of these species exhibits different color patterns, temperaments, and environmental preferences, but they all share the extraordinary biology that defines Chameleónovité.

Fascinating Facts about Chameleónovité

- A chameleon’s tongue can accelerate faster than a fighter jet engine relative to its size.

- Some species exhibit fluorescent bones, visible under ultraviolet light.

- Despite their ability to change color, chameleons are not truly “invisible.” Their color shifts depend on light, mood, and temperature — not a conscious camouflage mechanism alone.

- The smallest chameleon, Brookesia micra, measures less than 3 cm in length, while the largest can exceed 60 cm.

These facts highlight the extraordinary evolutionary journey of this reptilian family.

Conservation Efforts and the Future of Chameleónovité

The conservation of Chameleónovité demands international collaboration. Preserving their forest habitats, promoting captive-breeding programs, and educating the public about ethical pet ownership are key strategies.

Organizations in Madagascar and Africa are focusing on reforestation projects that restore degraded habitats, while global awareness campaigns work to curb illegal wildlife trade. Scientists also emphasize studying lesser-known species to understand population trends and ecological needs better.

The survival of chameleons is intertwined with the preservation of tropical ecosystems. Protecting them means protecting entire networks of life that depend on these forests.

Conclusion

The family Chameleónovité stands as a living testament to nature’s creativity. From their color-shifting skin and panoramic eyes to their slow, deliberate movements, chameleons embody both beauty and mystery. They remind us of the delicate balance of life within Earth’s ecosystems — and the importance of protecting it.

Whether admired in the wild, studied by scientists, or responsibly kept as pets, chameleons continue to fascinate humanity. Understanding and respecting them is the first step toward ensuring that these extraordinary creatures will grace our planet for generations to come.

FAQs

What does the term “Chameleónovité” mean?

“Chameleónovité” is the Slovak term for the reptile family Chamaeleonidae, which includes all species of chameleons known for their color-changing abilities and unique anatomy.

Why do chameleons change color?

Color change in chameleons isn’t only for camouflage. It also helps them communicate with other chameleons, regulate their body temperature, and respond to mood or stress. Specialized skin cells manipulate pigments and light reflection to create these color shifts.

Are chameleons good pets?

Chameleons can make fascinating pets but are not suitable for beginners. They require precise temperature, humidity, and lighting conditions. Stress or poor care can lead to serious health problems.

How long do chameleons live?

The lifespan of chameleons varies by species. Smaller ones live 2–3 years, while larger species like the veiled or panther chameleon can live up to 10 years with proper care.

Are chameleons endangered?

Some species of Chameleónovité are indeed threatened, primarily due to habitat destruction and illegal collection for the pet trade. Many are listed under international protection agreements.